Find this helpful?

This is just a small sample! Register to unlock our in-depth courses, hundreds of video courses, and a library of playbooks and articles to grow your startup fast. Let us Let us show you!

Submission confirms agreement to our Terms of Service and Privacy Policy.

Already a member? Login

AI Generated Transcript

Ryan Rutan: Welcome back to another episode of the Startup therapy podcast. This is Ryan Rota. I'm joined as always by my friend and the founder and CEO of startups dot com. Will Schroeder will. There's a lot of talk, maybe whispers about quiet, quitting in the media right now. It's become quite, quite a hot topic. But let's be honest about this. When did this actually start happening?

Wil Schroter: Everyone wants to think it started with remote work and, you know, I get it, I would argue and you tell me, I think it started the moment we gave people an internet connection at the office. Like as soon as they could, they could watch youtube instead of work. What Facebook, whatever it was game over as far as the office is all about productivity. What are your thoughts? Yeah. No, I'd

Ryan Rutan: agree. It was a distraction that had no boundaries. Absolutely. There's no limit to it. I tried. I, I looked for it. I could not find the end of the internet and that was in 1996 when it was a significantly smaller place. So, yeah, I, I totally agree. This is not, this is not a new problem. And look, we can point to all kinds of stuff, we can point to remote work, we can point to the pandemic. We can point to, you know, you know, wanting to become more intentional and purposeful with the work they're doing, which means they have to jettison their corporate job or, well, partially jettison it. But keep the salary, we could point to all of the layoffs and say that people are doing this is a security piece. They're like, well, look, you know, people are being fired out of cannons at, at Twitter right now instead of giving notice. So, uh yeah, it's cool to quiet quit. If we're going to be treated this way as employees, what respect do we owe to the company who's been paying us? They owe up until now. I would argue there's still a contract there and layoffs and firings are part of that contract. So I'm not buying into that entirely, but there's a whole bunch of shit that goes into this. But to your point, this is nothing new, right? This started before you or I could grow beards.

Wil Schroter: Yep. Uh I still can't grow a beard. So for folks that haven't heard of the term aren't exactly familiar what it is and it's relatively new when we're recording this. Quiet quitting is the, the idea that I'm still working at my job, I'm still getting paid. That part hasn't changed. Well, I should say I'm still getting paid. I'm not working at my job anymore. So again, this became more of a thing with remote work because people were saying, well, who's actually working and some people, it didn't take them long to realize I could sort of just not work and keep getting paid so much so that it started a whole other part where people started taking other jobs and start working other jobs entirely.

Ryan Rutan: Which is insane to me. But what could you hang on a second? I gotta, I gotta take this call.

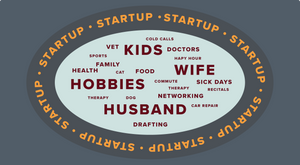

Wil Schroter: And so needless to say, as founders, you know, and people leading these companies, we're terrified of this idea, this idea that you, that we're paying, people are counting on people and in the background, they, they have quiet, quit altogether. And so in this episode, we're gonna talk about kind of what it is, but also how to stomp it out, right? Like when you find it, kind of what does it look like in your organization? What are the motivations behind it? And how possible is it to do? Because what I would say is this, everybody that's gone remote work has had an opportunity to kind of reset and change, kind of how they operate. There are a certain number of people, particularly in big companies. But, you know, also in startups that say, you know, if you take out my commute, if you take out lunch, if you take out senseless meetings, if you take out et cetera and all I have to do is that little thing that's actually my job two hours

Ryan Rutan: a day. It's actually not full time. I was spending most of my time getting to and from work in the water cooler. Yeah.

Wil Schroter: Yeah. And so all of a sudden their mind goes to the next place which is, well, you know, I've now got like, eight hours in the middle of the day to free it up. I only have to be on a couple of Zoom calls or something or, you know, check in or in Slack or something. I could kind of take another job too. Now, there's a little bit of irony there and that the people that are willing to quit are also ambitious enough to go take another job at the same time. But I gotta say, you know, I won't get specific but we had it happen with us, you know, we had it happen to a person making over $200,000 with us that quite quit. They basically took another job even though they're getting paid a ton of money and admitted it. This wasn't just something that, you know, we made up. We're starting to understand why the work was falling behind. And they, like, you know, to be honest, I've been juggling two jobs, but it's like, yeah,

Ryan Rutan: well, that's something you kind of need to let us know. I want to mention something here, which is that, to me, this is an extension. This is an exacerbation. This is an exponential increase. It's something that's always been a founder problem. It's always been an employer problem. Anybody who's ever had to lead people has had this challenge. And that's one of efficacy and efficiency, right? So this isn't a new thing. This is a new manifestation and, and a very extreme example of it, right? But like I go back to when, when I decided to take a break from technology and I launched my cafe because I just needed a break from tech. And I was like, I just want something simple. I had the same problems, right? I had this mantra. If there's time to lean, there's time to clean because I had fears about efficiency. I'm paying people by the hour. I don't want people standing around doing nothing, right? That wasn't quiet, quitting. But it's true. Shit wasn't working, which is what you're being paid to do here right now. In that case, it was pretty obvious. But I think this is it, this is an age role this goes. But this, this well precedes employment. I mean, let's say you are marshaling an army somewhere, right? Same kind of thing. Like wanna make sure everybody's focused, everybody's marching in the same direction, everybody's sharpening their sword the night before the battle. So this is nothing new, right? But this is a very interesting and weird twist on this and particularly when you take it to the full extreme where you've got people who are literally doing a new job. Well, not doing the other one. Right? Like I'm all about fractional work. I think that's totally possible if you have time and you have the gumption and you wanna do the side hustle, we preach this, right? You wanna do that? Cool. But you gotta do the first thing first before you start to do the second thing. That's not

Wil Schroter: OK. So there's a spectrum, let's lay this out. The spectrum goes from, I'm just not super productive slash, I'm distracted to, I'm straight up not doing my job. I actually just stopped doing my job at some point. I left and you're just gonna keep paying me until you catch on at one of the major credit bureaus. I just uh read about this. They actually used people's own credit reports to detect how many people in their organization had quit and taking. It was dozens of people. Oh my God, it was of people. You

Ryan Rutan: uh you're reporting double the income that we pay you somehow on that last credit request. Oh my God, that's by the way you could

Wil Schroter: do that. But it shows how rampant, right? And so I'll give you examples on both ends. We already talked about the, the far end of the spectrum where, where we had a person on staff and no ill will, by the way, I mean, it is what it is but we had a person on staff that, you know, literally took another job and was working two jobs. The other was in the early, early days of like bringing the internet to work. I know that sounds so oldy timing at this point. Right. But I'm talking like, I mean, that was decades ago but like I would say, 10 years ago and what I meant by bringing the internet to work, I meant you were generationally coming into work for the first time and you were always used to having the internet throughout your day. Yeah,

Ryan Rutan: you were bringing a version of the internet that had nothing to do with work to work. I think that was the major transformation for me was I was used to internet being at work. I've been for the last 25 years, but 10 years ago, all of a sudden, like Facebook showed up at work unless you're building ads or segmenting audiences or participating in groups. Like that's not necessarily something that I see as a necessary second monitor edition, right?

Wil Schroter: Like it was also a sign of the time is not just from the workforce that was coming in, but for us generationally who understood how to separate the two with two separate cases. This is about 10 years ago when we were first starting the company, we had some folks that worked for us, you know, they were relatively new. It's like their first or second job and maybe a year or two out of college. In one case, a person is, they've got two monitors on one monitor's Facebook, their feed and on the other monitors, the work that they do. And I remember asking him, I was like, hey, uh Facebook kind of there all the time. And they're like, yeah, why wouldn't Facebook be there all the time? That was the thing. You're literally not doing your job every time you turn your head over and, and again, I just want to be clear like this was just a moment in time. I would feel differently about it now. But I just want to point out right? And I'm pointing it out to say in the office, they weren't focused on work the whole time, right? I mean, they could turn their eyes left or right and they were either focused on work or focused on something that was not work another case. And both of these people were referencing if they ever listen to the podcast. We love you. So we do. So, yeah, you, you,

Ryan Rutan: you'll appreciate it. But thanks

Wil Schroter: for the story. Yeah. Thanks for the story. Thanks for the the other was comes to work and uh one day we look over and they're sitting there watching Netflix and I don't mean like watching it like in a little box, I mean, full screen watching Netflix. And dude, what are you doing? What's happening? Yeah. And they're like watching a movie, like

Ryan Rutan: I, I I, I actually had an extended conversation on a walk about this about how it helps to improve my focus. And I need that as a distraction from the other distractions. And I'm, I'm like, I'm trying to hear you. I'm trying to believe this. And I'm just like, no, I'm like, I remember at the time and I think we had this conversation again. This goes back a long time is 10 years ago. But I remember distinctly for the first time ever feeling like I had tripped and fallen head first into a generational gap. And I was just like, this makes no fucking sense to me whatsoever.

Wil Schroter: It was so far away

Ryan Rutan: from us. Fundamental. Yeah, but it seems to make total sense to you. So there's obviously a disconnect here. And so we had to explain things like it's not OK, at least for our company policy, right? Like this is not, we, we can, can't just have Netflix and Facebook open half the day to where, you know, at any moment at your discretion, you decide whether you're working or not. Like we came here for a purpose. This building when we used to do that when we used to rent buildings and, and sit in them to work together. That was why we were there, right? Netflix is for the building that you rent or own at home where you park your car and go to sleep at night. This is something different and that we had to explain that seem so ludicrous to me. And yet, and they took it well. Right. They're like, oh, ok. Ok. We can't do that. I got

Wil Schroter: it. But that was the beginning of the end is my point. That was the beginning of the end of where, where work in the workplace was considered, you know, critical or, or sacred or what have you. And, and we were on the wrong, you know, we were the dinosaurs in that equation to be clear now, fast forward, you know, a decade later and we're entering into remote work where there's, there's no supervision whatsoever. We're now in a new reality for some people. It's the only reality they've ever had, which is, we have no idea what people are doing at their computer all day long. Right. And so it invites this concern. But what if they're not working at all again and taking a step further? You know, what if they've actually quit? What if I get an hour a day out of the map? Right. Right. Right. So, let's talk a little bit about what we can do to actually start to get a sense for whether people are, are actually checked in or checked out because, you know, as a startup where every single person matters, the idea of having someone checked out is critical to our business. These are smaller teams, somebody's checked out at Disney, sort of who cares. It's not gonna change anything. Right. They're checked out with us, our products won't get shipped, our sales won't get made. I mean, it's, it's a huge problem.

Ryan Rutan: Yeah. I mean, on a percentage basis, right. If you get a team of 10 and two people are checked out 20% of your workforce isn't there. That's about the deal to absorb. Right. Yeah. And, and it's interesting because you would think that at a smaller company, like a startup, that this would be a near impossibility. Well, maybe you wouldn't think that I thought this, I thought this, I thought, you know, this is not something that is really going to be a pressing problem for a lot of startup companies and yet it turns out it was, and, and maybe for some pretty specific reasons. So I, I've got a few recent examples of founders I talked to as this topic started to pop up, I just started to, you know, kind of randomly throw it into conversation. Like, so look, is quiet, quitting. Something that you're worried about is something you're facing. They're like, oh my God, like, you can't imagine what's going on right now. Like, we've got a team of 15 and three quarters of them, of them, our moonlighting. But during daylight hours. Right. And, and it's a major distraction and, like, part of that is that, you know, we're a startup company we're paying maybe below market wages. Our benefits aren't the best. There's lots of like these justifications and yet this isn't what you said you would do the day you signed up for the job, but the founders are having a hard time fighting this off. And to your point, this is really, really tough, right? If one employee in a massive company, right, you're like, you know, Jasmine, you didn't really give it your all today during the Aladdin parade at, at Disney. Not a huge deal. Right. You know, we can work hard tomorrow if 25% of your workforce, 50% of your workforce at a startup company who by the way is still trying to figure all the shit out and nothing's working, right? And it makes it even harder when nobody's working on anything. This is a disaster of epic proportions at a really small scale.

Wil Schroter: You know, something that's really funny about everything we talk about here is that none of it is new. Everything you're dealing with right now has been done 1000 times before you, which means the answer already exists. You may just not know it, but that's ok. That's kind of what we're here to do. We talk about this stuff on the show, but we actually solve these problems all day long at groups dot startups dot com. So if any of this sounds familiar, stop guessing about what to do, let us just give you the answers to the test and be done with it. Yeah. So in my eyes, I use the same management technique now that I've always used. And it's kind of this simple, it's simple, but it's so effective waterboarding. Waterboarding. Yes. The technique is this simple, good players. People contributing never shut up about it. OK. And I don't mean that to be in a negative way, they're never quiet right now. That doesn't mean that sometimes people don't put their heads down and get some work done. But for a prolonged period of time, people that are really good at what they do where they're contributing hard, don't forget to mention it. Right?

Ryan Rutan: If things are working or aren't right? Because even if things aren't going well, right. It doesn't mean that, you know, you have to be, you're only sharing success. But if you're sharing nothing, it's a pretty good indication that that's an accurate reflection of what's actually happening in your day, right? Why are you sharing? Nothing? Nothing's happening.

Wil Schroter: It's always an indication, right? Where there's smoke, there's fire. We talked about this actually dedicated a whole episode to this where

Ryan Rutan: there's no smoke, there's

Wil Schroter: nothing. So one of the things I mentioned was years ago, I worked with this uh huge car dealership franchise uh network and I asked them how they managed all their franchises. This is back like in the two thousands and they said we walk around. I was like, ok, ok, that's very vague. What do you mean? They said we go to each dealership and we walk around, we put our finger on the car and we rub it to see if there's dust or, you know, a dirt on the car, on the car lot. We look around to see who's standing at each of the different positions. The sales people are supposed to be at, versus taking smoke breaks or whatever it is that they do. And that's how we know when things are going. Right. I'm like, so, so, you know, K P I S, you don't have like, you know, manager reports like, well, we have those but those only tell you so much. It's the details, right? That tell you a lot this morning, I'm working out with a buddy of mine, another founder and he had to let someone go and we're, we're talking through it and he said the same thing. He's like, you know what? But in the last couple of calls he gets on the call and he, he's not prepared. I try to message him like a little bit after hours, he's got his notifications turned off, not the end of the world, but these all start to become these compounding things. One or two, you might be able to overlook. But when it's three or four good people don't have three or four problems

Ryan Rutan: starts to form a pretty strong pattern. Right.

Wil Schroter: Exactly. Exactly. As we were working out, I was telling him, I was like, you know what I know this in sales we have all of our sales change. Right. And I love our sales people. So this is no knock against them, actually has nothing to do with them. Specifically. When things are going well, when people are selling like crazy sales channels are going nuts. Right. It's a busy channel. It's a high five fest. Right. It's

Ryan Rutan: never, there's never 15 slack messages that say I didn't sell anything. Me neither. And I probably won't tomorrow. I didn't yesterday either. Right. It never happened,

Wil Schroter: right. But when it's tumbleweeds in the Slack channel, I don't even have to look at our numbers. I know we know what's going on, right? Like I said, good players and you know, some of this performance, some of this timing, good players are always performing and you could always tell they're shipping code, right? They're bringing in visitors, they're closing sales, they're completing projects like you don't have to wonder when this stuff stops happening. They're not working exactly that

Ryan Rutan: this goes back to performance measurement. I mean, that and that's what the guy with the car dealership was talking about, right? Which was that? Those were K P I s, right? Dust on a car may not seem like a K P I in the modern sense, right? If we're thinking about a, a company, but it sure as shit is, right. A dusty car is a failed K P I, right? People not at their posts is a failed K P I this is why I only buy cars from those places that have the towers in the middle where there's a foreman who's watching over everyone, prison work camp style who's ready to drop anybody that tries to run off the lot.

Wil Schroter: That, that's actually straight up terrifying. So I think that from my standpoint, I think you, you've got two ends of the spectrum, right? I think you've got one end of the spectrum which is just the little things that you see. Right. You know, for those of you that, that you slack, it's 9 30 or whatever time you start, we start at nine. Right? And, and their little slack thing isn't green the end of the world. Right? Sometimes happens, maybe you're running to the doctor or something. But when it happens, time after time after time again,

Ryan Rutan: specifically when it's like every time I go looking for you, it's like that, which means I'm not looking at it all the time, right? This is something that happens sometimes. So if out of the eight random samples, six times, I couldn't find you. That's probably a problem. But

Wil Schroter: those are little things, those aren't K P I s right. That's just if there's, they're somehow a little bit off when people are on their game, you don't notice those things when people are engaged when they're focused, right? You don't notice those things when you're in like let's say a zoom meeting and everybody's in the meeting. People that love what they do probably want to contribute. They probably want to talk about it. They're probably making a joke or engaging conversation. People that are checked the hell out. They don't do any of that. I

Ryan Rutan: love the ones where it's like they actually turn off the camera.

Wil Schroter: Yeah. Oh, when you go to a turn off camera bill and, and sometimes there's good reasons to do it. It's usually indicative

Ryan Rutan: when you turn off camera and come back on camera with a bowl of cereal. I'm less pleased about it, right? Like

Wil Schroter: we've had that so many times. And so the way I look at it is again, it's, it's simple. I look at it and say, OK, there is a pattern of behavior for, for engagement, there's just a pattern of behavior and for founders that are listening to this going, you know, now that you mention it, like some of this stuff is starting to kind of add up when somebody's consistently late for meetings or, you know, no showing when they're consistently taking like a disproportionate amount of time off and I'm all for people taking time off. But when people are looking to kind of check out and go do something else, they start taking a lot of time off. Why wouldn't you? Right. Because there's no consequence, right? You start no, these patterns of behavior that usually indicate that something isn't going, right. Conversely, if they're like, dude, I can't find any more hours in the day. Like I'm like, I'm so buried right now. It's usually not part and parcel with quiet quitting.

Ryan Rutan: No, no, unless it's because my other job, my other two jobs are taking up so much of my time. I literally have no time left for this. Yeah. But again, that's the extreme case and I hope it represents the minority. I hope

Wil Schroter: two ends of the spectrum, one end of the spectrum we're gonna talk about here is just what we said. It's just those little indicators, right? It's the dust on the car that tells you if somebody's not, not washing these things like they're supposed to right now, the other end of it is actually just straight up K P I s which we haven't talked about, you know, deliberately. But when we talk to a lot of founders, just a lot of organizations, they have what I'm gonna call Macro K P I S. Here's what the business overall needs to be doing. Here's our site conversion rate, you know, here's our sales conversion rate, et cetera. Maybe here's some of our shipping timelines, et cetera. What they tend to not be as good at are micro K P I S O K R s, you know, whatever, whatever system you're following where they say, what does this person have to get done by Friday? Every Friday, right, Ryan, you, you know, I've talked about this endlessly. We track everything as to what do we need to get done by Friday? Why? Because it's a timeline you can't fake. It's,

Ryan Rutan: yeah, there's very little, it's not like a 20% overrun. Even if there's a 20% overrun on that project. That's a day. Right. That's tolerable. We can fix that. We can work around that. Right. But when you're, when you're looking at time frames of 34 months, five months, 20% of that, it's a lot,

Wil Schroter: right. I would argue that this isn't even about quiet quitting. This is just about good management. However, what I would say is actually this is a great example. You know, we write articles behind a lot of this stuff and when I was writing this article about, you know, should I worry about quiet quitting? What I was trying to do is I was trying to poke holes in our own organization at startups dot com to say here's here are areas that, you know, we would improve if we could. What was interesting? Every single person at our company has a responsibility either to uh a client directly, which in our case would be a founder. Uh somebody that they need to talk to on a regular basis, a specific deadline within five days or some sort of a dollar metric, the amount of money they've sold, et cetera. It's really hard, it has been. And the more I thought about it again, as I kind of analyzed our own business it's really hard to skate for very long here. Partially because we know what to look for, but partially because even if you're working two hours a day, if you're hitting your, your metrics, you're good right now. This

Ryan Rutan: is a slippery slope, right? It's a slippery slope there for

Wil Schroter: sure. And so, you know, you could look at that and you could say, well, yeah, but if, if you ask, um, somebody, let's say on the Dev team, um, our Deb team is great, but ask somebody on our Deb team, how long will it take to do something? If they only use essentially a 2 to 3 hour estimate? If they say it's gonna take me eight hours, it only takes them two hours and you're using those testates, then how are you gonna know in truth be told? You may not, right? There's a, a little bit of slop there, but that said, you don't need to be that detailed. You need to be more like if they said this was gonna take a month and really it should be taking a week. We got some issues, right? And so most of the stuff we can put some sort of quantifier to and for the stuff that we can't, we try to look for the smoke, you know what I mean?

Ryan Rutan: Yeah. Yeah, you gotta look for the smoke. And I think that it's rare anymore that I find things that are, that you really can't quantify in some way, shape or form. Right. That, yeah, at a startup. Because there's so many things because we're in so many binary situations, right? Where it's like it either exists or it doesn't. Right. So, if it doesn't exist now it exists, we have it, it's a process we didn't have now we have it. Right. So many of them are, are these nascent efforts that are just really easy to track. Right. They, they come into existence, you know, as we, as we move further along, it gets a little bit harder, but kind of to your point in our organization, at least most of what we do is accountable to someone and highly measurable, right? And, and we've used examples like sales is the easiest one because it's so measurable, it's purely measurable, right? Like it's literally just a figure, other things like DEV become a little bit harder. But again, it's the feature exists or it doesn't, right? And then you have things that, that go along with that, that where you start to pair up metrics, which is OK. How long did we say it was gonna take? How long did it actually take? Yes, it exists now, but it took twice as long. Why? Right. So that we can adjust for that next time and so forth. And so having these, these management frameworks like K P I like, OK, K R are super, super important because I think it allows you to get that level of detail further down. Like you said, most companies have these big, big North star metrics that they're pointed towards. But the reason that we hit those is by hitting shit tons of tiny little K P I s or O K R s, right? Or the reason we don't hit them is because we're not right. And one of the main reasons for that is people being checked out and not engaged. We're just not clear on what they're supposed to do either way. It's a management problem and it's an efficiency problem. Back to my early point. This has always existed. This is just another reason and an avenue for it to manifest. But the same problems always existed, we have to be good at helping our people do what needs to be done and measure it and understand and track it, right. It's not easy, but it's simple.

Wil Schroter: And I would argue that to your point, this is nothing new but in an age where we actually don't have quite the visibility we used to. And I think it gave us a little bit of confidence that, well, everybody's in the building, right. And to be fair, it was helpful back in the day because knowing that everyone was in the building, they probably weren't watching Netflix and doing their laundry or at least in the building, there's, there's some level of commitment,

Ryan Rutan: one or two cases. But

Wil Schroter: yes. Right. And so I think based on where we're at now. Yes. Are we worried that people are quiet, quitting? Yes. And by the way, we should be, I think this is an incredible call to action on the behalf of all leadership to take a moment and to say, you know what, I'm not ok with running my organization loose. I've got to make sure that every single person in the organization to your point knows what they need to do and they need to know exactly what their metrics are week over week. So they can deliver. If they're quiet, they're not hitting their metrics. I can jump on it. But if I don't have those metrics in place, then I was screwed from the start. So in addition to all the stuff related to founder groups, you've also got full access to everything on startups dot com. That includes all of our education tracks, which will be funding customer acquisition, even how to manage your monthly finances. They're so much stuff in there. All of our software including Biz plan for putting together detailed business plans and financials launch rock for attracting early customers and of course, fund for attracting investment capital. When you log into the startups dot com site, you'll find all of these resources available.

No comments yet.

Start a Membership to join the discussion.

Already a member? Login